A touching memoir about a husband’s losing battle with cancer carries with it a message for healthcare industry revenue cycle professionals: become more transparent.

Amanda Bennett is no dummy when it comes to healthcare. An editor at Bloomberg, she won a Pulitzer Prize in 1997 for unraveling the labyrinthine mysteries of AIDS funding. But all her knowledge about the healthcare system did not prepare her for what would be the most personal journalistic investigation of her life – deciphering her late husband’s medical bills.

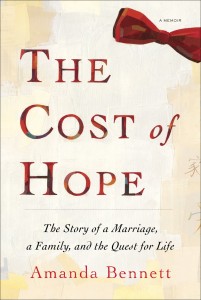

Bennett is the author of The Cost of Hope, a memoir of her late husband’s losing battle with cancer and her subsequent quixotic quest to make sense of how and why it cost so much.

When she added it all up, the total bill for her husband’s 7-year battle with kidney cancer was $618,616. It was a shocking number, but the months-long investigation into those costs brought her to the realization that there needs to be more transparency when it comes to medical bills – transparency that may not be fully possible because of the inherent cost structuring of healthcare in the United States. Among the challenges she identified:

- Different prices for different patients. Procedures and treatments are priced differently depending on whether a patient is insured or self-pay, and if insured, what kind of insurance they have. Over the course of his treatment her husband underwent more than 70 scans, and prices for those scans were all over the map. “Why is it that the same procedure by the same doctor should cost 15 different amounts?”

- Insurance discounts. During his treatment Foley received the drug Avastin, which the hospital billed at $27,360 per dose; Blue Cross paid $6,665.40. “I don’t get it,” she writes. “If the insurance company can negotiate a price cut of more than $20,000 a dose, then where does the rest of the money go? And why do hospitals and doctors and other health care providers sometimes take 20 percent of what they ask, and sometimes 80 percent?”

- Pricing hidden by contract. “A hospital can bill and charge what they want and get what they can, depending on how good the negotiator is on the other side,” Bennett says. Bennett was unable to learn the formula behind hospital billing rates and insurance reimbursements, as both sides said that information was confidential, protected by contract between the hospital and the insurer.

Bennett admits that transparency in healthcare pricing and billing is better today than it was when her husband was first diagnosed in 2000, but it is in its infancy. In a telephone interview with insidePatientFinance.com earlier this week, Bennett says, “There’s a trend toward greater transparency, but I’d say we’re at about 1 percent instead of 99 percent.”

Why the book

Why the book

Bennett wrote the book because she, like many people, was haunted after her husband’s death by the question, “Did I do the right thing?” Was there more she could have done to keep her husband alive longer, she wondered.

Unlike the average person, she had the knowledge and skills to go back in time and deconstruct her husband’s illness. “I can go back and get all the records and have the skill to analyze them,” she says. She could interview all the doctors, the pathologists, and the hospitals to find out what happened. And if she got stuck, she could recruit other investigative journalists to help.

Bennett spent months poring over her husband’s medical records, reexamining the doctors’ every decision. Her conclusion? “I did the inevitable thing,” she says. “There’s nothing that I did that was wrong, but here’s where we get back to the love story: I wanted to do everything – whether it cost a million dollars or it cost two dollars – I wanted to do everything to keep this man alive.”

Foley’s treatment did not cost a million dollars, but from Bennett’s perspective it was far from cheap. Her investigation revealed that, for the most part, her husband received good medical care. In the end she found that her husband had not been wronged by the healthcare system. It was the system itself that was wrong.

Amanda Bennett © Natasha Cholerton Brown

The price of healthcare

Bennett writes that she and her late husband were both good shoppers. “Both of us buy sensible things at good prices after serious consideration,” she writes. “Yet we racked up $36,000 in [medical] charges without a thought.”

The reason it was so easy? “We had fabulous health insurance,” Bennett says. “We are part of the reason health care costs are going up. We didn’t even think for a second about how much everything cost. The doctors didn’t think about it, the hospital didn’t think about it, so it was an irrelevant thing.”

“The biggest issue is lack of transparency: If you can’t see it, you can’t compare it.” The answer, at least part of it, is for healthcare organizations to explain to patients what their healthcare costs – what it all costs, she says.

Transparency may not be possible, according to Bennett, because of a healthcare system “in which prices are set as in a [giant] bazaar,” she writes. “A system in which $600,000 in bills becomes $200,000 in payments, and as much as possible of the cost of care for people who can’t or won’t pay their bills is tucked into the negotiating space between those numbers.”

Bennett sees no relief in sight. Our interview was conducted on the eve of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on healthcare reform. “My experience is really interesting because it doesn’t matter what the Supreme Court decides,” she says. “The Supreme Court will decide on how we insure … the 15 percent of people who don’t have any insurance.” Bennett is one of the 85 percent who do are insured, and “my experience speaks to why it is that the costs are being driven up so fast that we now use up 17 percent of GDP,” she says

“The Supreme Court decision, whichever way it goes, will not solve the issues I’m talking about,” Bennett says.

![[Image by creator from ]](/media/images/2015-04-cpf-report-training-key-component-of-s.max-80x80_F7Jisej.png)

![[Image by creator from ]](/media/images/New_site_WPWebinar_covers_800_x_800_px.max-80x80.png)

![[Image by creator from ]](/media/images/Finvi_Tech_Trends_Whitepaper.max-80x80.png)

![[Image by creator from ]](/media/images/Collections_Staffing_Full_Cover_Thumbnail.max-80x80.jpg)

![Report cover reads One Conversation Multiple Channels AI-powered Multichannel Outreach from Skit.ai [Image by creator from ]](/media/images/Skit.ai_Landing_Page__Whitepaper_.max-80x80.png)

![Report cover reads Bad Debt Rising New ebook Finvi [Image by creator from ]](/media/images/Finvi_Bad_Debt_Rising_WP.max-80x80.png)

![Report cover reads Seizing the Opportunity in Uncertain Times: The Third-Party Collections Industry in 2023 by TransUnion, prepared by datos insights [Image by creator from ]](/media/images/TU_Survey_Report_12-23_Cover.max-80x80.png)

![Webinar graphic reads RA Compliance Corner - Managing the Mental Strain of Compliance 12-4-24 2pm ET [Image by creator from ]](/media/images/12.4.24_RA_Webinar_Landing_Page.max-80x80.png)